I realized recently that when I changed hosting for LarryShort.com, I accidentally left in the dust the only copy to be found on the Internet of my 1981 article in Athletes in Action Magazine, “Beyond the Matterhorn.”

In 1980 (before his death in October) I interviewed (in my role as a writer with the Public Relations Department at our alma mater, Biola College) my friend and classmate Tobin Sorenson regarding his record-breaking adventure of a solo speed climb conquering the North Face of the Matterhorn in the dead of winter.

At the time of my interview Tobin was of course alive and well, and engaged to be married to a close friend of Darlene’s and mine from our church, Elizabeth (Biza) Sorenson. (Same last name, not related.)

Tobin’s tragic death from a climbing fall in Canada in October occurred just a few short months before he and Biza were to be married.

Tobin’s story was incredibly inspiring and his tragic death hit all of us at Biola very hard. It was a few months later, shortly before I graduated from Biola (a year after Tobin did) that I decided to honor Tobin and further share his story by taking another whack at the article and submitting it for publication to Athletes in Action Magazine. The magazine, then related to Campus Crusade for Christ (now known as CRU), graciously accepted and published the article, which then won a “Best Personality Feature of the Year” award from the Evangelical Press Association in 1981.

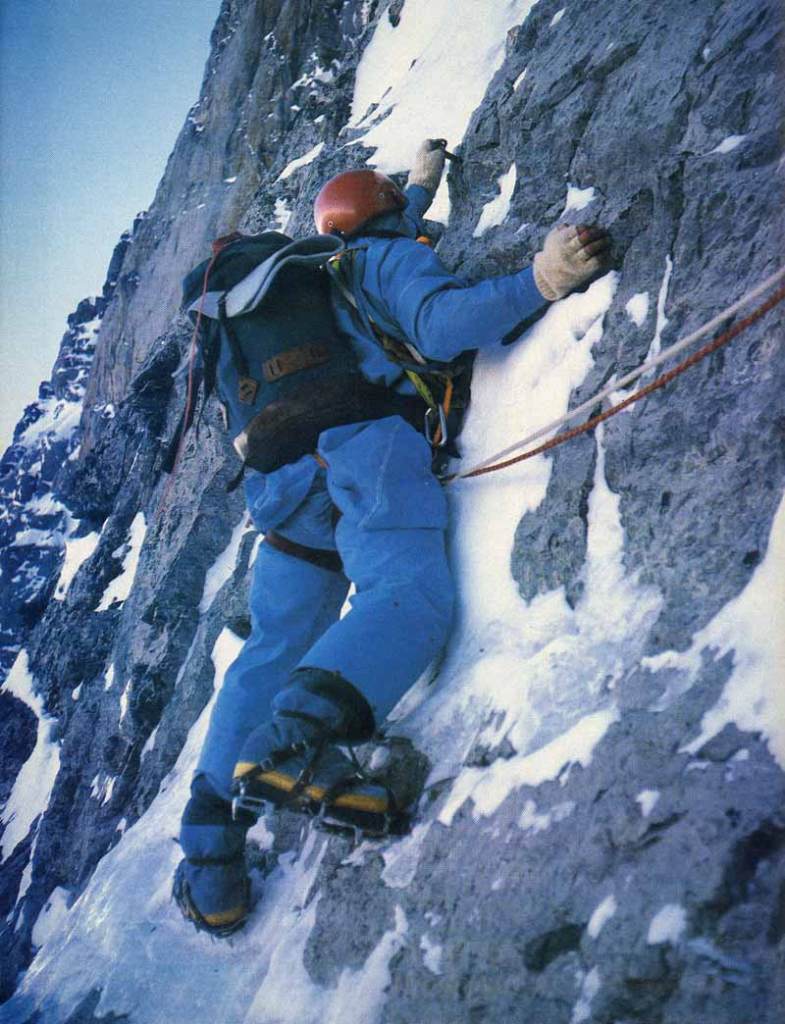

As there is no truly “online” version of this article (Athletes in Action having been closed some years later), I am posting here for all who are interested a scanned version of the printed article. (The article was three pages in length, including the feature image of Tobin climbing which graces this blog post. The other two pages are below. Following these is the text of the article, for the sake of search engine optimization.)

Athletes in Action Magazine, Spring 1981, CDC 00267, page 33

Beyond the Matterhorn

Only two men had ever accomplished solo climbs of the Matterhorn’s North Face before Tobin Sorenson made his. Yet life provided Sorenson with an even higher summit …

BY LARRY SHORT

I got off the train in Zermatt, Switzerland. I had my climbing gear on and my knickers, and I looked completely out of place because everyone else had the finest ski gear, the latest styles. They were there in Zermatt for the skiing holidays. I was there to climb the Matterhorn.

As I was walking through the streets of Zermatt, the sun was setting, off to the right side of the mountain, and it was turning the slick ice of the North Face into a red flame. It bathed everything — the trees, the cottages, even the ice on the cobblestones beneath my feet — in a glorious redness.

People were walking down the other side of the street, coming down from the slopes, exclaiming, “Hey, what do you think you’re going to do? Climb the Matterhorn?” They would laugh and say, “You can’t do that! Where’s your partner?”

Only two men had climbed the North Face of the Matterhorn solo in the winter, an Italian and a Japanese fellow. And they both received medals of valor from their countrymen.

As I walked on, I began to cry. I had never felt so alone in my life. I had begun climbing at 15, working my way up through mountains in Southern California, then in Yosemite and Colorado, and finally in the Alps. Later I would climb mountains in Canada, Peru, Australia and New Zealand. But never had I felt so small and alone.

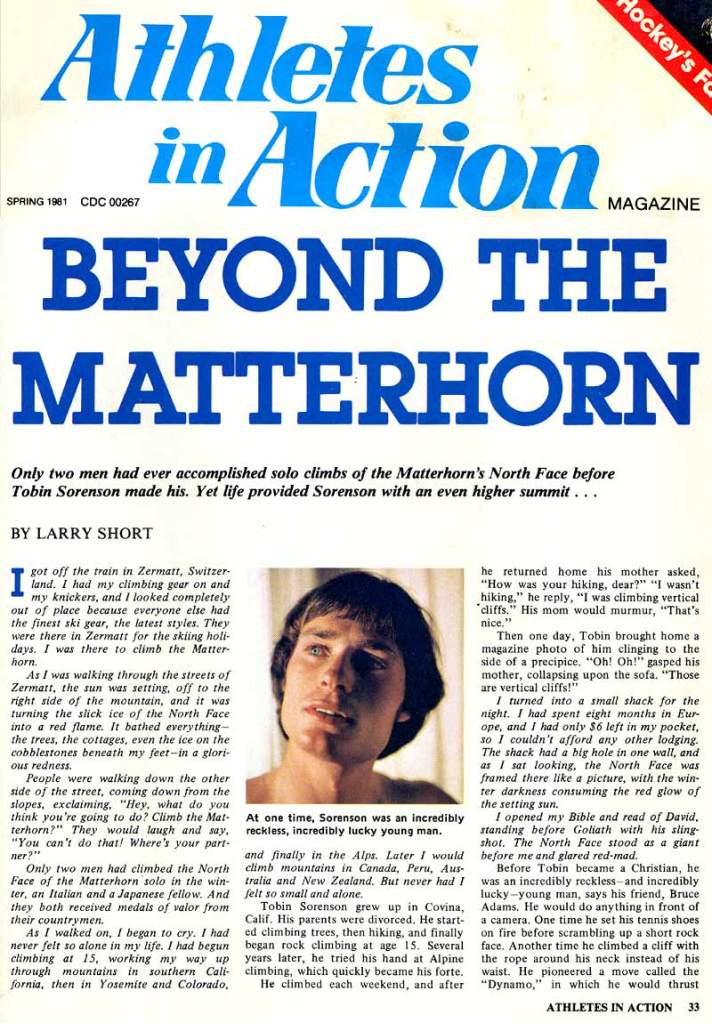

At one time, Sorenson was an incredibly reckless, incredibly lucky young man.

Tobin Sorenson grew up in Covina, Calif. His parents were divorced. He started climbing trees, then hiking, and finally began rock climbing at age 15. Several years later, he tried his hand at Alpine climbing, which quickly became his forte.

He climbed each weekend, and after he returned home his mother asked, “How was your hiking, dear?”

“I wasn’t hiking,” he’d reply. “I was climbing vertical cliffs.”

His mom would murmur, “That’s nice.”

Then one day, Tobin brought home a magazine photo of him clinging to the side of a precipice. “Oh! Oh!” gasped his mother, collapsing upon the sofa. “Those are vertical cliffs!”

I turned into a small shack for the night. I had spent eight months in Europe, and I had only $6 left in my pocket, so I couldn’t afford any other lodging. The shack had a big hole in one wall, and as I sat looking, the North Face was framed there like a picture, with the winter darkness consuming the red glow of the setting sun.

I opened my Bible and read of David, standing before Goliath with his slingshot. The North Face stood as a giant before me and glared red-mad.

Before Tobin became a Christian, he was an incredibly reckless and incredibly lucky young man, says his friend, Bruce Adams. He would do anything in front of a camera. One time he set his tennis shoes on fire before scrambling up a short rock face. Another time he climbed a cliff with the rope around his neck instead of his waist. He pioneered a move called the “Dynamo,” in which he would thrust himself completely free from the rock in a leap for a promising crack or ledge. But Tobin’s climbing fetish was far more than just an outlet for recklessness.

The mountains were Tobin’s “cathedral experience.” They were a picture of the nature of God. Their towering heights were a grand arrow pointing God-ward, to a summit where one might stand as in God’s hand. To cling desperately to the immovable stone thousands of feet above the earth was to embrace God, he thought.

“It was climb, climb, climb,” Tobin reflected. “Don’t stop, and don’t look back. Climbing was my god, and I looked to it for my meaning, my social life, my every need.I finally got to this point of fame I had always wanted, but when I stood up on this little mountain of mine, this summit of fame and ability, I began to see the emptiness of it all. There was still a giant gap in my life.”

The next day I started up toward the base of the Matterhorn. Snow was knee-deep, and it was about 25 degrees below zero. The weather was turning bad, with snow-laden clouds pushing in above. I walked all day, then stopped for the night at the foot of a glacier. I slept until about 3 a.m., then started up the ice.

The sky was clear, but darker than one could imagine, with a sea of brilliant stars watching me trudge across the glacier. There was a jagged ridge of peaks to my right, and to my left loomed this tremendous North Face, 4,000 feet above my head.

The moon was behind the mountain, and its shadow engulfed me, extending all the way back to the village, wrapping me in hte mountain’s own deathly blackness.

That sheer vertical wall was seizing a hold on my brain now, thundering, “What are you doing?! YOU’VE GOT TO GO BACK!” I knew that once you start up the North Face, and you get about a thousand feet up, there’s no turning back.

The glacier came to an end, and I was confronted with solid rock. It was about 5:30 a.m. I dropped to my knees on that ice, slumped against the wall and cried out to God. “Oh, God, I’m so afraid, I’m so afraid. What am I to do?”

One day, Tobin packed his bags and went home to deal with this special mountain, the problem of his own meaninglessness. He met Adams, a climber who had an extra “something” in his life that gave it purpose and meaning. Tobin soon discovered that the “something” was a person — Jesus Christ, God Himself revealed as a man. Tobin wrestled with God for many months before trusting in Christ to forgive his sins and to be his Lord.

Sorenson’s joy: clinging desperately to immovable stone high above the earth.

The young climber’s recklessness turned to an intensity of life that astounded those who knew him. He began to attend a small Bible school; then he joined other young people in evangelistic work behind the Iron Curtain. It was during this 1977 trip to Europe that he embarked upon his celebrated season in the Alps. Before he left Europe, he was practically a national hero in Switzerland and France. He traveled on a lecture circuit, then he enrolled at Biola College, a Christian school in La Mirada, Calif. It was there that he met a girl of the same last name, Elizabeth Sorenson, and they were engaged to be married in January of 1981. Before graduating from Biola, Tobin said he was going to give up serious climbing in a few years.

God’s answer was as immovable as the stone, but soft and full of love. “If you turn around now, if you go back, you’ll forever be sorry. You won’t for years and years have the chance to return to this place again.” Somehow I knew that in my heart. So I stood up, and as frightened as ever, I started climbing.

I never climbed so well in all my life. It seemed I was born for this moment. In nine hours, I stood on the summit of my dreams, the summit of the Matterhorn.

Adams recalls that all of Tobin’s friends were relieved at his intention to quit climbing, which he announced last year, three years after conquering the Matterhorn. Very simply, says Adams, they were afraid for his life. “Tobin knew that, as one of the most talented alpinists in the world and a steward of the art, he must push himself into very dangerous situations. He believed with all his heart that God created him to climb mountains.

“Everyone paces himself a certain way, assuming that he has so many years left to live. Tobin paced himself as if his death were very near …. He didn’t want to waste even a single moment of his life.

“I’ve never known anyone who had such a real grasp of the tragedy of sin. He had an intense desire for personal holiness. Many of the best climbers have a reputation for arrogance, but he didn’t see being a climber as his chief identity. He was most proud of being a child of God.”

That single-minded love for God came through clearly. A message Tobin gave to some fellow Christians helps convey his commitment: “I have tried often to say that in Christ we must live radically. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a carpenter or a musician or a mechanic or a preacher or a mountain climber — what we need is people who have the guts to step out in boldness, committed to such an extent that their own lives are of no concern …. Somehow we think that Paul and Isaiah are still around and that their lives will suffice. They aren’t, and they won’t. It is us. Neither is it Luther or Wesley. It is us.”

Neither anymore, we can now add, is it Tobin Sorenson. It is us. For on Oct. 5, 1980, Tobin fell 2,000 feet to his death from another North Face — that of Mount Alberta in the Canadian Rockies. He was climbing solo on a patch of icy vertical rock when he fell, so no one knows exactly how it happened. Attached to his body was his rope, which he had become accustomed to using only in the very tightest spots.

Tobin climbed mountains. He was acknowledged as one of the best in the world. Yet he was a different mountain climber from most. Many climbers seek immortality through becoming one with the rock, but they die, reaching the summit and yet without God. Tobin recognized God and died in His embrace, not at one with the rock but at peace with the God who made the rock.

Working toward his bachelor’s degree in communications, Larry Short has crammed four years of college into six at Biola, where he was a classmate of Tobin Sorenson. Larry also serves as director of the Evangelical Student Press Association.

Leave a comment